SALUTE TO VETERANS: Today, I remember

FORT WORTH, Texas (Christian Examiner) – "Warren E. Evans, age 96, or Huntingburg, Ind., died July 6, 2015, at The Springs at Tanasbourne senior living center in Hillsboro, Oregon."

So began the brief obituary of an American patriot.

It was not the kind of obituary that gets printed in the famed pages of the New York Times or the Wall Street Journal.

Mr. Evans was not a titan of industry. He was not a famous actor. He wasn't a long-serving politician. He didn't invent anything, as far as I know. Many were not aware of his passing. Most never knew he existed.

If not for a chance encounter, I wouldn't have known the name either. To me, Mr. Evans was Capt. Evans.

In 2011, while attending the U.S. Army Ranger Hall of Fame induction ceremony at Fort Benning, Ga., I went to visit the Ranger Memorial on the post, not far from its renowned Airborne School. While I was taking a few pictures at the memorial a car pulled up in front of it and parked.

An "old timer" got out of the car. He stood up tall, even though he was ever so slightly bent by his years. He stepped up onto the curb and straightened the beret he wore with his civilian clothes as he made his way up to the memorial. His long, white eyebrows curled upward toward the rim of the beret and he smiled a faint smile as he walked by. His steps were small and slow. He stopped every once in a while to read the names on the bricks under his feet.

I noticed then that he had a large handkerchief in hand and when he stopped he dabbed the tears from his face. He moved on toward the center part of the memorial, looked at the large bronze dagger on it for a minute and then went and sat down quietly on the bleachers. He sat there for a few minutes just looking at the memorial.

After a while, I went over and talked to him.

"Hello, Ranger," I said. He chuckled and said, "Yes, sir, that's me." I sat down next to him and introduced myself. He shook my hand.

"You know, my name is on that wall – right over there," he said, pointing at a granite block not far away. "You might not be able to see it from where you are. That's me, Warren Evans."

"You are in the Ranger Hall of Fame?" I asked.

"Yes. You see that monument there? That's for the 1st Ranger Battalion. That was my unit. I was one of Darby's original Rangers. I was his senior NCO (non-commissioned officer). I even told him off once. I said, 'Sir, you've missed your landmark, and we're way off course.' He said, 'No, we're not!' But I insisted that we were and I told him he could go ask everybody else and they'd agree. Well, he did, and he was wrong. That was November 8, when we landed in North Africa."

"Two days later," he said with a smile, "I was a 2nd Lieutenant. I received a battlefield commission. All of our officers were dead."

"Capt. Evans" went on to tell me that he had made all four North African landings, participated in several significant nighttime raids (including one 12 miles behind enemy lines), and then the landings at Sicily, Salerno and Anzio. When he finished, large tears filled his eyes but he pushed them back with the handkerchief.

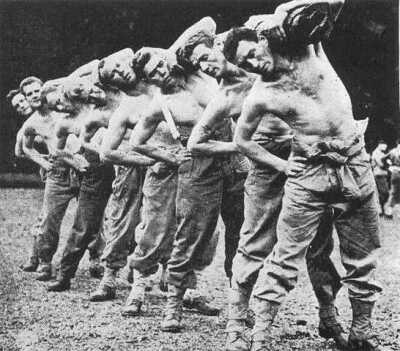

"Three-and-a-half years I was in Europe. I was 225 lbs. when I left – an All-American athlete – but I was 140 lbs. when I returned home. Coming home was the hardest thing I'd ever done. It didn't feel right to be home in a bed when I knew my friends were buried a continent away. I still think about it -- every day I think about it."

"Well, they invited me down for this ceremony tomorrow," he said. "I bet they thought I wouldn't come. I'm 93 years old. But these are my friends, so I drove 600 miles to be here. This is probably my last 'hoorah.'"

I asked him were his home was, and he told me it was originally the Dakotas, but he'd moved around after the war, working with Rolston Purina. He finally landed in Indiana.

He had made the trip by himself. He mentioned his wife, but I didn't ask if she was alive. I thought the answer was obvious by his look of sorrow when he talked about her.

I found out later that his wife, Francis, had died a few years before. The other pieces of his story also fell into place, such as why he lost so much weight during the war. Capt. Evans was a prisoner of war for 15 months. Starving and force marched from camp to camp, he attempted escape three times. He was successful on his third attempt, just days before his scheduled execution as a spy.

"Nobody would believe all of the things that happened to me if I told them," he said. He paused and looked down, biting his lip. "I really don't think anybody cares anymore anyway."

I was both saddened and incredulous. How could people not care about this sweet old man's story? How could they not care about what he suffered for us? How could they ignore his contribution to our heritage of liberty?

Then, the little voice in my head whispered the answer to me.

No one listens to him anymore. No one asks about his service. And as much as he doesn't want to talk about it, he wants to talk about it. He is tired and he is weary. His memories haunt him and without someone to talk to about them, he's left with only his memories and him. There's a battle that takes place in him every time he thinks about his combat experience. Why can't he forget? Why can't he let it go?

He can't, I think, because it is what made him who he is. It makes him appreciate life. It makes him appreciate liberty, secured by the very friends he visits at the memorial. It makes him realize that all of the years he held his beloved wife were a gift from God. It makes him proud. If he hadn't done what he did, who would have?

Certainly, there would have been another soldier in another place, but he wouldn't have played the part of Capt. Warren Evans in the history of our nation.

I patted Capt. Evans on the knee and I said, "Sir, I haven't forgotten. I thank God for what you did."

Still tearful, he said, "I guess I will remember this until I die."

"I believe you will," I said. "But I will remember this conversation as long as I live."

I asked Capt. Evans if he was a man of faith. He told me he "sure" was, so I asked if I could pray for him. He said "yes" and he reached up and pulled off his beret and clutched it in the hand opposite his handkerchief.

I prayed that "the God of all comfort" would visit him and remind him not of the horrible circumstances surrounding the deaths of his friends, but of the good times he had with them. I prayed that he would be able to find peace and understanding. I prayed that he would find rest from his dreams in the arms of Christ.

When I finished, Capt. Evans looked up at the sky and said, "Let it be so, Lord."

When I drove away from the monument, Capt. Evans had not moved. He was still sitting there, watching the sun's long shadows creep over the monument. And just before he was no longer visible, he reached up with his handkerchief one more time to wipe away the tears.

Dr. Gregory Tomlin covers the intersection of politics, culture and religion for Christian Examiner. He is also Assistant Professor of Church History and a faculty instructional mentor for Liberty University Divinity School. Tomlin earned his Ph.D. at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, and also studied at Baylor University and Boston University's summer Institute on Culture, Religion and World Affairs. He wrote his dissertation on Southern Baptists and their influence on military-foreign policy in Vietnam from 1965-1973.